Alimentary Machinations

誇り食品機械学派ウェブサイト

Remembering Asanuma Inejirō, Yamaguchi Otoya and the turbulent postwar period

On 19 January 1960, the arguably most controversial law in the Japanese Diet was passed. The passing of the “Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan”, or “Anpo” for short, caused widespread protests and was probably the only time in Japanese postwar history when a complete spectrum of society rallied to a cause and protested against what was seen as a bulldozing of parliamentary democracy. The then Prime Minister of Japan, Kishi Nobusuke, utilized the democratic mechanizations to force this bill and treaty through the Diet.

The political and geopolitical ramifications of the Anpo only served to reinforce and to revise a peace treaty that had been signed in 1951 (Treaty of San Francisco), which saw the castrating of Japanese geopolitical power and their sovereignty. The Americans were legally able to exert their influence and interests onto domestic Japanese politics without consequence. After the signing of that treaty came the bloody May Day protests, which was arguably the bloodiest protest in Japanese postwar history. The passing of Anpo also justified the occupation of Okinawa, a territory to be used for America’s overseas adventures.

The May Day Protests against the Treaty of San Francisco

In the context of the Cold War, it forced Japan to be on the side of America. In close proximity were the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China, both of which viewed Anpo as a direct threat. There was a concern that America viewed Japan as nothing but collateral. Protests started to ramp up in May 1960 when the Soviets announced that they would strike at any base that sent US spy planes. Japan, castrated and its geopolitical sovereignty virtually non-existent, was forcibly made a target. The early postwar period was wrought with protests like these, and tensions in Japan have never again reached this high a level.

The 1947 Japanese constitution is another controversial entity. It was not even written by the Japanese themselves, it was written by Americans. His Imperial Majesty, under that Constitution, has no autonomy and is entirely subservient to the secular government, which in turn is subservient to the Americans. The Imperial House cannot even alter its own rules for succession without passing a law through an entity ruled by social contract. The American-written Constitution utterly smashes imperial autonomy and disregards Japanese tradition, and it is done so against the will of the Japanese. One could argue that we live in the nadir of Japanese civilization, where Japan is subjugated, humiliated, the spirits insulted and divinity disrespected. In many ways, a neverending 1945.

Now four paragraphs in, and not once have I made mention of the namesake of the article. It is important to be aware of the Japanese political environment at that time, the circumstances under which Asanuma Inejirō, the then chairman of the Nihon Shakaitō (Japanese Socialist Party), took his political stances and why it is he made overtures to Mao and the Soviets. It goes without saying that this also applies to Yamaguchi Otoya.

Yamaguchi Otoya lookin’ sad for some reason

Everyone knows the story behind the assassination. In Hibiya Public Hall, central Tokyo, on 12 October 1960, Asanuma Inejirō was giving an innocuous speech when a youth named Yamaguchi Otoya plunged a yoroi-dōshi deep into Asanuma’s side. Shortly after, Otoya committed suicide in prison, not before writing “Service for my country seven lives over. Long Live His Majesty the Emperor”.

The infamous picture of the assassination taken by Nagao Yasushi

At first glance, without knowing the context, this “fascist” kid just killed a “socialist” leader. One can react to that first impression in many ways. One way could praise the “fascist” kid for saving Japan from Communist internationalism and from starvation, saying he’s the reason why people can watch anime today. Another way would be to countersignal that praise, and mourn the death of a “fellow comrade”. One more would just be to use it as an example against violence in politics, and so on. But this is merely a first glance. Let’s look deeper.

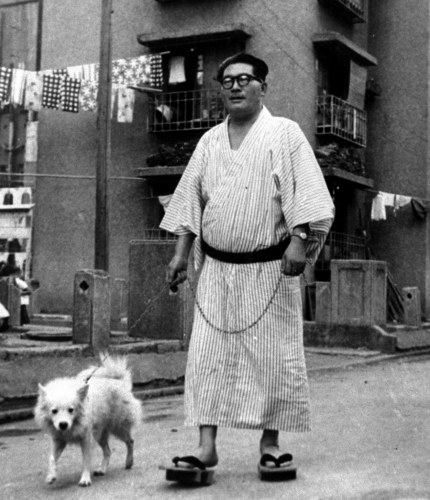

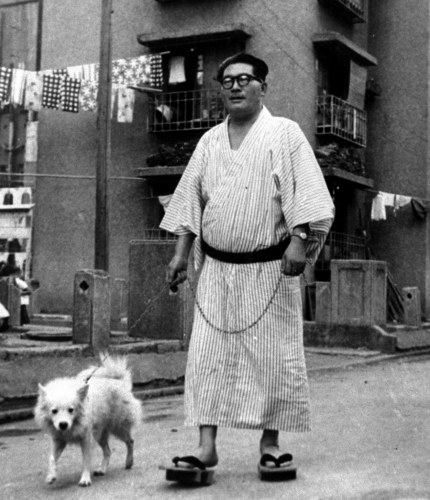

What is almost never said about Asanuma Inejirō is how it is he lived his life. He was born on 27 December 1898. He attended Waseda University in 1918, joined school socialist organizations and took part in several protests against the military. He also spent his days in university protesting for support for peasants and nationwide labour problems. On a more amusing and lighthearted note, it’s also noted that he always had a big frame for a body, and joined the sumo club during his time in university. Later on in his ventures in politics, he would adopt the nickname Ningenkikansha, or “Human Train” due to his huge body and loud voice.

Asanuma Inejirō walking his dog

Asanuma graduated from Waseda University in 1923 with a degree in political science and economics. In 1925, he became the secretary general of the Nōminrōdōtō (Farmer’s Labour Party), which was cracked down upon by the Taishō government in the same day of its formation. After this event, he began veering towards a “national socialism”. To be clear, it is more “National Bolshevik” than it is a Hitler-esque movement. In the early 1930s, Asanuma joined the Shakai Taishūtō (Social Masses Party), which was the only leftist party in Japan that was allowed to exist at the time. Asanuma came to support a pro-military, yet pro-agrarian stance, as the party itself cultivated ties with the Hideki Tōjō-led Tōsei faction within the Imperial Japanese Army.

In 1936, he was elected to the House of Representatives for the first time, and in 1940 the Shakai Taishūtō was merged into the Taisei Yokusankai (Imperial Rule Assistance Association). He was appointed Deputy Director of the Temporary Election System Research Department (long title, I know) within the Taisei Yokusankai. In 1942, he declined his candidacy in the Taisei Yokusankai general elections due to the mental anguish caused by his friend Hisashi Aso, who had died two years earlier. He was also the head of the Shakai Taishūtō.

After the war, Asanuma was appointed head of the Japanese Socialist Party. There were many divisions within the party, the most prominent of all between the radical Marxist-Leninists and the national socialists with more centrist social democrats. This division was finally made concrete in 1951, when the Treaty of San Francisco was signed. The Japanese right-wing did not protest and agreed with the signing of the treaty, while the Japanese left-wing was outraged and opposed it vigorously. Asanuma ultimately opposed the treaty, and the Japanese Socialist Party was split into the Rightist Socialist Party and the Leftist Socialist Party, and Asanuma was made the secretary-general of the Rightist Socialist Party. However, the party reunified in 1955 and Asanuma was once again made the secretary-general of the unified Japanese Socialist Party.

In 1959, Asanuma made his overtures towards Maoist China and called the United States a shared enemy of Japan and China. His overtures caused much controversy within Japanese politics, and drew criticism from even other socialist politicians. Logically, it makes sense for Asanuma to look to Maoist China for geopolitical realignment, given that they were the most powerful anti-American polity in the region. And that is, as far as relevant history is concerned, the end of Asanuma’s story. The most important thing here is that not once did I say that Asanuma renounced any of his actions in the past, therefore he never renounce his nationalistic ways. He also never renounced his reverence for His Imperial Majesty or being a part of the Yokusankai.

Asanuma Inejirō with Mao Zedong, 1959

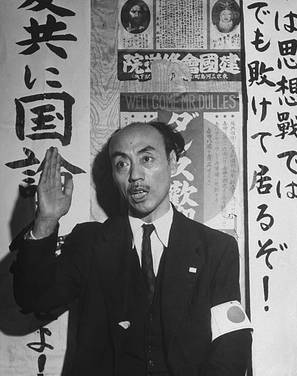

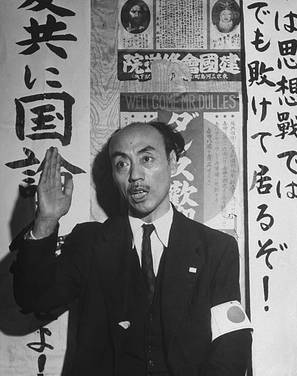

These overtures drew the ire of one Yamaguchi Otoya, who lambasted Asanuma as a traitor for making these overtures. His plan to murder Asanuma was not surprising, given that his violence had been ramping up from the year before. For example, he had injured a police officer, threw smoke bombs at protesters, and trespassed just to name a few. Because of his age however, he had only received probationary sentences. He had joined Bin Akao’s Dai Nihon Aikokutō (Great Japan Patriotic Party), which was one of the right-wing groups that had frequently clashed with Anpo protesters.

It is important to note that the Dai Nihon Aikokutō had been pro-Anglo-American since the 1920s, and that right-wingers saw communism and socialism to be detrimental to the Japanese national body politic (kokutai). Another important thing to note is that the yakuza were generally right-wing aligned and were utilized by Americans and the ruling Japanese party (Liberal Democratic Party), racketeering against Anpo protesters and anyone anti-American in general.

Bin Akao

Thus Yamaguchi died a child soldier of the uyoku dantai, an ultranationalist zealot. The actions that Yamaguchi took shook the entire country to its core, and inspired many right-wingers at the time because such a direct and public political action had not taken place since the February 26 Incident in 1936. Now, remember the previous paragraph in which I said Asanuma never renounced his nationalist ways, and revered the Emperor to the end. It is then here we can make the argument that Yamaguchi and Asanuma were actually fellow ultranationalists.

The most pressing matter of the Cold War was geopolitical stance, either with the US, the Communists or with neither. This is where Asanuma and Yamaguchi ultimately differed, merely which entities they thought were most harmful to the Japanese body politic and to His Imperial Majesty. Asanuma saw the American occupation as more harmful, Yamaguchi (and the right-wing in general) see China, Korea and communism/socialism to be more harmful. Thus, Yamaguchi lambasted Asanuma in that manner.

However, everyone in the contemporary Japanese far right generally agree that both Asanuma and Yamaguchi were morally upright people who held true to their principles. The act of assassination itself is beyond reproach in my opinion, the problem with it is regarding the target of assassination, the consequences of Yamaguchi’s actions and the validity of the reasoning behind his motivation to kill, however pure his heart may have been.

Indeed, these things must be questioned, considering Asanuma’s prominence and the potential for a pro-Japanese sovereignty movement. The stance that Asanuma took at the time was that Japan would be geopolitically independent, free from American servility. The consequences of Asanuma’s assassination was the castrating of any pro-Japanese sovereignty movement, which afterwards only existed in the New Left (Zengakuren) and more radical Marxist dissidents.

If one wishes to prioritize Japanese geopolitical (and imperial) sovereignty, I would think that Asanuma’s national socialism combined with anti-Atlanticism was the most appropriate theoretical-practical orientation for the Cold War. Especially given how corrosive the US occupation of the Home Islands were to the national body politic, in how servile Japan has become. In contrast, Akao Bin and Yamaguchi Otoya were patriots as well (the former had distanced himself from yakuza racketeering), but the Dai Nihon Aikokutō’s anti-communist and Atlanticist orientation is, to me, unacceptable.

Asanuma Inejirō's grave in Tama Cemetery, where Mishima Yukio is also buried

As it is indeed the anniversary of Asanuma’s assassination, I wrote this in tribute to Asanuma’s and Yamaguchi’s acts of patriotism, especially Yamaguchi’s valorous final act. It is tragic to me that one patriot deemed it necessary to assassinate another patriot, they both revered the Emperor to the end. After this tragic state of affairs, there is nought but lament for the death of a patriot, almost as if a member of the family killed their kin.

Return...